ISIS’ attack on the Ariana Grande concert in Manchester on 22 May was particularly heinous because it specifically targeted teen and pre-teen girls. It represents some of the most twisted and hateful ideology known to mankind: Islamist jihadism (IJ). Obviously, this was not the first IJ attack on an entertainment or hospitality venue. Nor did it achieve the highest casualty count. But are we aware of how often these types of attacks happen? The following statistics from 2016 – 22 May 2017 help explain the threat and clarify the capabilities and intentions of IJ groups, particularly regarding entertainment/hospitality venues. It is a wakeup call.

To briefly clarify, the following data and analyses apply to IJ attacks only. Select target locations here include entertainment, food/beverage, lodging, and sports venues. Religious structures and shopping sites such as daily markets and malls were excluded.

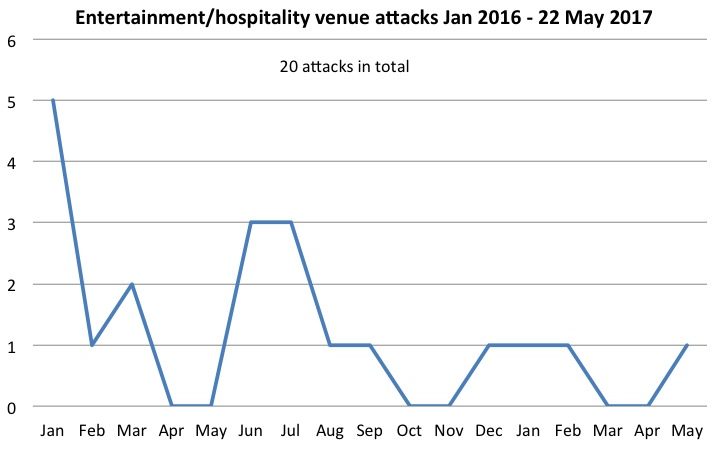

Timeline: From January 2016 – 22 May 2017, there were 20 IJ attacks on entertainment/hospitality venues around the world. There were at least 17 attacks in 2016, and there have been as many as three so far in 2017. Statistically, this translates to nearly one every month, a solid operational tempo. For this short time period, the trend line is down, but the casualty rates are beginning to creep up (see below).

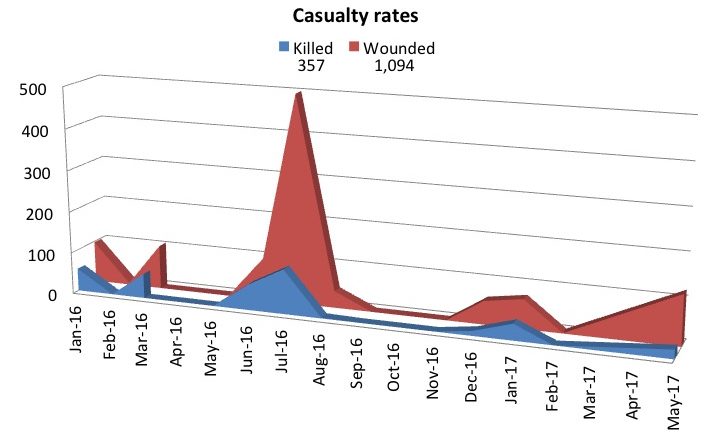

Casualties: The total number of casualties for this IJ target set during this timeframe was 357 killed, and 1,094 wounded. In military terms, this equals about two companies and a reinforced battalion, respectively. Comparatively, there were multi-day periods during major WW II battles where US forces sustained such casualty rates. But in this ongoing Islamist war, these are civilian casualties, they are spread out over about a year and a half’s time, and they are global. They have a slow, erosionary, and significant impact on society. Over time, such attacks lower societal morale, cause a loss of faith in government and security forces, trigger ethnic and religious tension, increase internal government friction, and divert government spending. These are classic irregular war effects. It is war by attrition, war by exhaustion.

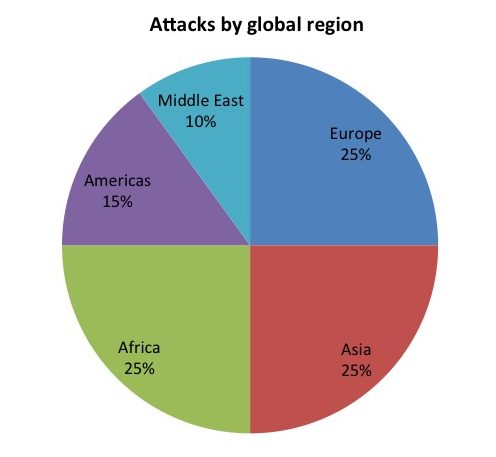

Global attack geography: Geographically, IJ terrorists spread out their attacks on entertainment/hospitality venues during the established timeframe. Europe, Asia, and Africa each suffered five such attacks. In the Americas, there were three, and in the Middle East, there were two. So this is not simply a “Middle East or Muslim problem” that is “over there.” It is global, and it is certainly happening in the West and in developed countries.

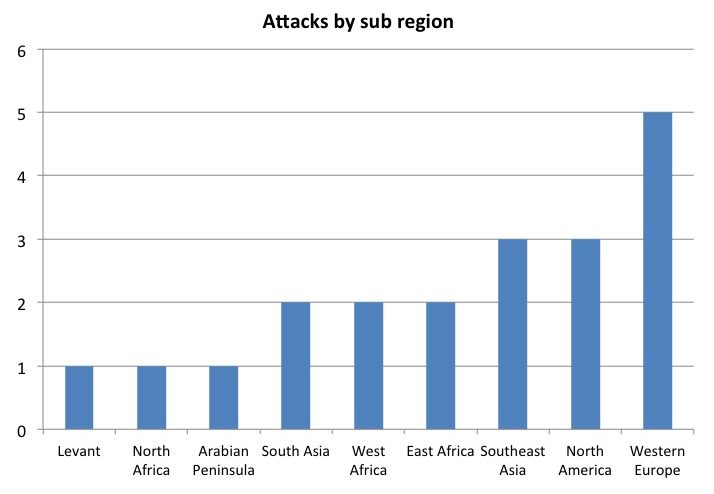

Sub regional attack geography: Sub regional data reinforces the broader global data. This demonstrates that IJ terrorists have invested considerable personnel, intelligence, operational expertise, logistics, and financing into attacking entertainment/hospitality venues in Western Europe, North America, and Southeast Asia.

Sub regional attack geography: Sub regional data reinforces the broader global data. This demonstrates that IJ terrorists have invested considerable personnel, intelligence, operational expertise, logistics, and financing into attacking entertainment/hospitality venues in Western Europe, North America, and Southeast Asia.

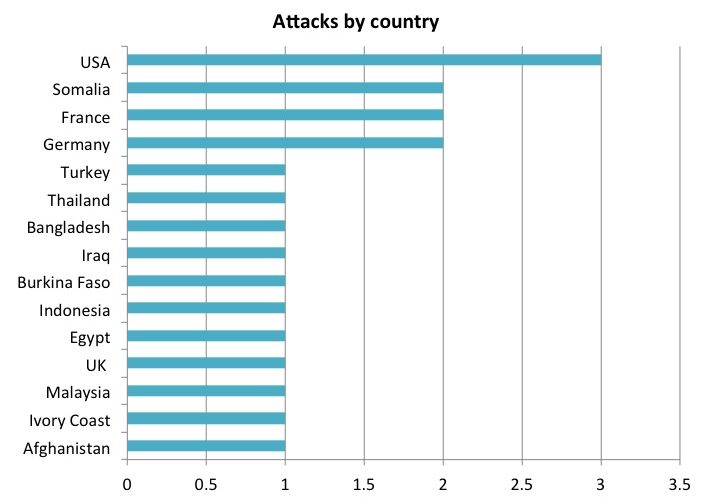

Country attack geography: The above geographic conclusions are further bolstered by the data on attacks by country. The US suffered three (Orlando, Florida; Seaside Park, New Jersey; and Columbus, Ohio.) Germany, France, and Somalia each suffered two. Afghanistan, Egypt, Indonesia, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Iraq, Malaysia, Bangladesh, Thailand, Turkey, and the UK each had one.

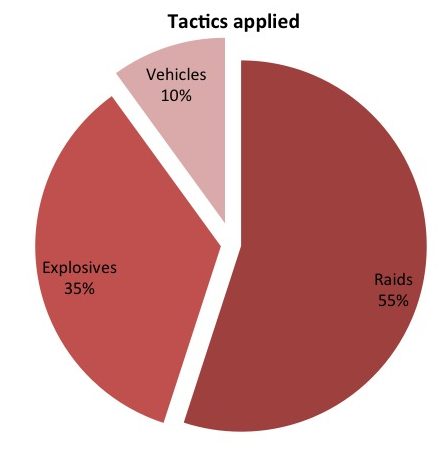

Overall tactics applied: IJ terrorists used three types of tactics on entertainment/hospitality venues during the 2016 – 22 May 2017-time period: raids, attacks using explosives, and vehicular homicide.

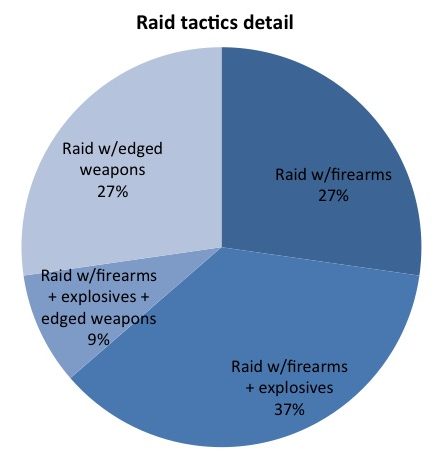

Raid tactics: Raids consisted of either a single person or a group attacking a location and then escaping or fighting to the death. It takes audacity and the willingness to murder scores of civilians face-to-face to raid an entertainment/hospitality venue.

In seven cases, groups did the attacking, and in four cases, individuals did. The latter, when firearms are involved, are more commonly known as “active shooter” situations.

The 12 June 2016 attack on the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida, is a prime example of the latter. Here, a single shooter raided the venue with a semi-automatic rifle, killing 49 and wounding 53.

The 15 January 2016 raid on the Cappuccino restaurant and Splendid Hotel in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, is an example of a “classic” terrorist raid. Here, as many as six members of AQIM (al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb) armed with assault rifles and explosives raided the aforementioned cafe and hotel, killing 30 and wounding 56. They also set the hotel on fire.

In most raids, the attackers used firearms and/or a combination of firearms and explosives, like a car bomb and AK-47s. For example, the 1 June 2016 raid on the Ambassador Hotel by a small squad of AK-47 wielding, al Shabaab terrorists began with a massive car bomb. The casualty rate was 13 killed and 40 wounded.

In three raid cases in the given timeframe, however, the terrorists just used edged weapons, like knives and machetes.

As an example, on 12 February 2016, an Islamist jihadist acting alone attacked the Nazareth Restaurant and Deli in Columbus, Ohio, with a machete, injuring four before police shot him. The 1 July 2016 raid on the Holey Artisan Bakery (restaurant) in Dhaka, Bangladesh, however, is also typical. Here, five ISIS-related terrorists took over the venue with firearms, explosives, and knives. Firmly in control, the terrorists methodically slaughtered scores of hostages over several hours until security forces stormed the establishment. The final casualty rate was 20 killed and 50 wounded.

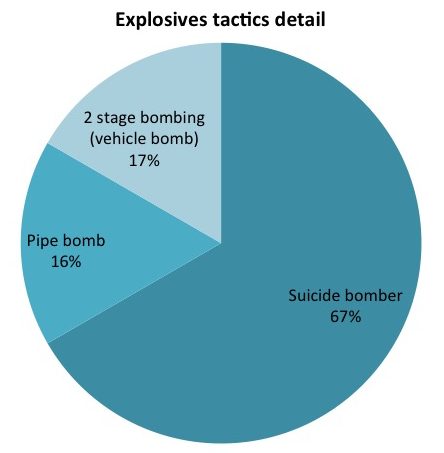

Explosives tactics: Attacks with explosives consisted of suicide bombers, hidden/planted bombs, a two stage bombing that included a vehicle bomb, and a grenade attack. Planted bombs require tradecraft skillsets regarding circumventing/tricking security and surreptitious placement of an explosive device. Suicide bombs require much less. Grenade attacks require speed in the attack and egress.

An example of a grenade attack comes from Kuala Lumpur. Here, on 28 June 2016, two ISIS terrorists on a motorcycle drove up to the Movida night club/sports bar – much of which is open to the street – and hurled in a grenade before speeding off. No one was killed by the blast, but eight were wounded.

Regarding bombings, and besides the Manchester case, on 24 July 2016, a suicide bomber attacked Eugens Weinstube (Eugene’s Wine Bar) in Ansbach, Germany, next to an ongoing music festival, injuring 15.

Vehicular tactics: Vehicular homicides used cars, vans, or trucks to plow through crowds of people. Vehicles and pedestrians, then – two elements common to every society on earth – are all that is needed; that and a murderous ideology. It is a relatively new tactic, and it can achieve high casualty rates. In fact, of all 20 cases cited here, a vehicle attack – the Bastille Day attack in Nice, France – achieved the highest casualty rate: 87 killed, and 434 wounded. (Usually, the street where this attack occurred, the Promenade des Anglais, is a normal street, but at the time of this attack, it had been turned into a festival venue, so it was included in the attack data.)

The broader tactical analysis for all these attacks is this: it is not just the tactic, but also the target, that dictates casualty rates.

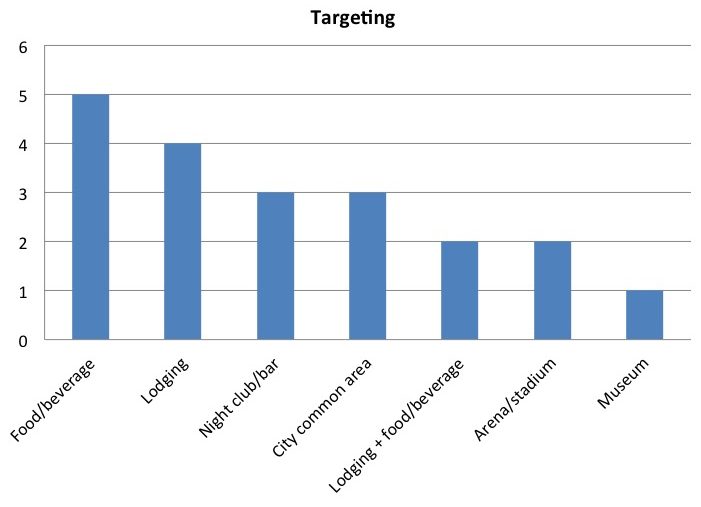

Targeting: As for targeting – the person or thing that terrorists want to destroy – there were five cases of attacks on food/beverage venues, four cases of attacks on lodging (one case involved two hotels in a single attack), and two cases of attacks on combined lodging-food/beverage venues. There were three cases of attacks on night clubs/bars, and three cases of attacks on urban common areas like boardwalks and promenades. Examples of the latter include the attack in Nice and the pipe bomb attack on the boardwalk in Seaside Park, New Jersey, during a Marine Corps charity race, which injured no one.

As for the rest of the targets attacked during the 2016 – 22 May 2017 timeframe, there were two attacks on stadiums, and one attack on a museum.

Hotels and restaurants are popular targets in part because civilians in these places are contained in defined spaces, and to terrorists, attacking them is like shooting fish in a barrel. These places are moreover high traffic areas and are regularly full, so the opportunity for attack is nearly always present. The other venues, like stadiums, are packed with civilians on a less frequent basis, and even average event security can dissuade at least some terrorism, so attacks on these places has been less frequent.

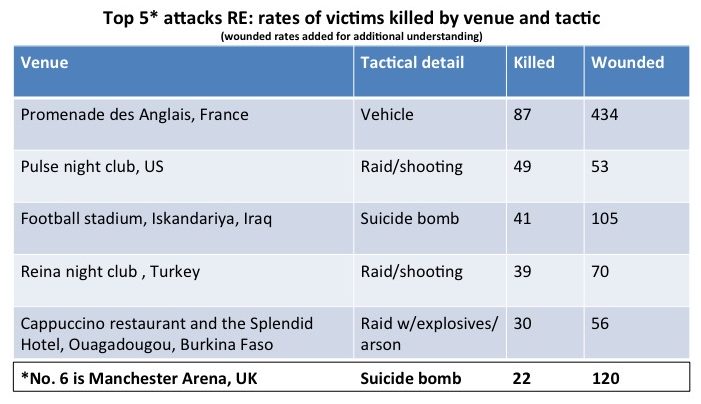

Kill rates by venue and tactic: As stated, casualty rates not only depended on the tactic used, but the civilian capacity of the venue – as in, was it packed with unsuspecting people at the time of the attack? Above are the top five attacks that reaped the most number of killed during the 2016 – 22 May 2017 timeframe. Manchester was number six.

Conclusion – understand the tactics, but also master their ideology

The attack on the Manchester Arena was not uncommon regarding the venue itself. (The mass targeting of young girls was, however.) IJ terrorists see entertainment/hospitality locales as high payoff targets, and they will continue attacking them. Their goal in attacking these and other civilian establishments is to break down their targeted societies slowly but surely, and exhaust them into some kind of politico-religious compromise and/or submission, even if it is incrementally over a long period of time.

Additionally, IJ groups might squabble and even kill each other – the temporary ISIS vs. al Qaeda fight in Syria, for example – but they are increasingly seeing their war as united in politico-religious ideology and global end goals. Many nation states, on the other hand, largely see terrorist attacks in general as singular incidents carried out by cells on a per-country basis. The United States is a classic example. It has scores of national security professionals and multitudes of pundits who see terrorism in this regard. Additionally, causing nation state governments to argue amongst themselves – to politically devour themselves – is an effects-based aspect of this strategy, and it is effective. The political fallout and finger pointing after each entertainment/hospitality attack demonstrates this point.

Strategically, allowing such attacks to go unchecked only empowers IJ groups to do more. Simply absorbing these types of attacks and accepting them as “the new norm” is folly as well, not to mention malpractice. Doing so fails to understand the multiple, profound impacts of irregular warfare.

By the time the US entered the Vietnam War in earnest in 1965, for example, communist assassins were already staging about 1,000 assassinations a year throughout South Vietnam. They targeted government civilian administrators, police officers, staunch civilian supporters of the southern government, etc. Society had already been destabilized, and simply fighting the communists with military force was not enough. There needed to be dramatically enhanced intelligence to identify and neutralize the enemy, heightened physical security, and, most importantly, counter political warfare. It was political ideology, after all, that drove the communist assassins to kill.

What is happening around the world now is similar. But instead of a single country like Vietnam, it is global. Tackling this threat requires a full understanding not only of the enemy’s tactics and violent strategy as demonstrated here, but their ideological intentions as well. It took ideology for the Manchester terrorists to build and deploy a suicide bomb against little girls. Aside from improved security across a wide spectrum, it will take a massive counter ideology campaign to help defeat this threat.

Copyright © Muir Analytics 2017