Mozambique insurgency: Analysis of combat capabilities and intentions

The insurgency in Cabo Delgado province in Mozambique is one of the world’s most aggressive and violent insurgent movements. It has taken over most of Cabo Delgado and has reportedly defeated most, but not all, government operations launched against it since 2017 (late summer 2021 Rwandan military offensives excluded.) The insurgency has attacked scores of villages, local businesses, and international corporations, most of which are invested in the massive gas field off Mozambique’s northeast coast. The BBC says the fighting has killed 2,500, though figures from other sources run as high as 3,600. The fighting has also displaced 700,000 people. In May 2019, Muir Analytics gave a short, utilitarian brief on Mozambique’s insurgency, along with threat indicators and warnings (I&W,) to Lloyd’s of London’s Terrorism and Political Violence Panel. What follows is the longer, written version of that briefing. The focus here is combat capabilities and intentions, only. Despite Rwandan troops being deployed in recent months to combat the insurgents, and despite the Rwandan’s initial success, the insurgents remain a viable threat, and this brief remains relevant.

A quick note on methodology and sources

Several think tanks and media outlets have produced datasets or comprehensive lists of Mozambique’s insurgent activities, including, but not limited to, the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED,) the Organization for World Peace, the International Crisis Group, the Daily Maverick, Relief Web, Caboligado.com (which uses much ACLED data,) and AllAfrica.com. From datasets and article lists like these, Muir Analytics identified over 150 significant operations (out of scores of other, seemingly smaller operations) that help shed light on the group’s combat capabilities from the late 2017-spring 2021 timeframe.

This briefing does not delve into the origins of the insurgency in Mozambique, although Muir Analytics researched the subject, and it does appear connected to radical imams that have preached Islamist jihad in Kenya and Tanzania. This information is relevant and contributes to the analysis of the group’s intentions.

It should be reiterated that this briefing was for underwriters, not military planners, or security providers, though the intelligence here could be used by the latter to some degree. Additionally, the insurgency’s personnel, training, intelligence, logistical, financial, communications, and other staff functions are not addressed here. Finally, this is an open source-based analysis, and because press access to Cabo Delgado has been limited, the analyses are limited, and they should be updated as new information sources become available.

Who are the Mozambique insurgents?

The initial name of the insurgency in Cabo Delgado was Ahlu Sunna Wal Jamsa (ASWJ, aka, Ansar al-Sunna.) This roughly translates to “the congregation that follows the Sunna.” The Sunna is a collection of the sayings of the lifestyle of the Prophet Mohamed. It can also be translated as following the path of the Prophet Mohamed. In the context of an armed movement – especially a violent one that attacks civilians – following the Sunna is typically associated with Islamist jihadism. ASWJ began major offensive operations in October 2017.

Since then, the group has reportedly aligned with ISIS, and government and private security professionals have labeled it everything from Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP,) the Islamic State’s Wilayat Gharb Ifriqiyya (ISWAP,) ISIS-Mozambique, or simply ISIS and its other name variations. Then there is the supposition that the insurgents consist of multiple groups that use a variety of these names. To avoid overcomplexity, Muir Analytics will refer to the insurgents as ISIS-Mozambique until there is a decisive reason to do otherwise.

As an aside, some locals and Mozambique soldiers call the insurgents “al Shabaab.” Reportedly, while interacting with villagers, the insurgents have referred to themselves as al Shabaab, but this seems to be local slang.

There is no evidence so far that Mozambique’s insurgents are THE infamous, Somalia-based, al-Qaeda-affiliated, al Shabaab. For clarification, there is another group of the same name in Somalia that is anti-Islamist jihadist.

Numbers of insurgents

According to Mozambique subject matter expert Johann Smith, Director at Heracles Consulting LLC, ISIS-Mozambique has approximately 3,500 personnel. Jasmine Opperman of ACLED assesses that there are 19 cells and a minimum of 2,500 fighters, says The Africa Report. These numbers seem to be a combination of fighters and support personnel. The ratio of fighters to support personnel is not known. There are no numbers on how large or small the group’s auxiliary support network (local support) is.

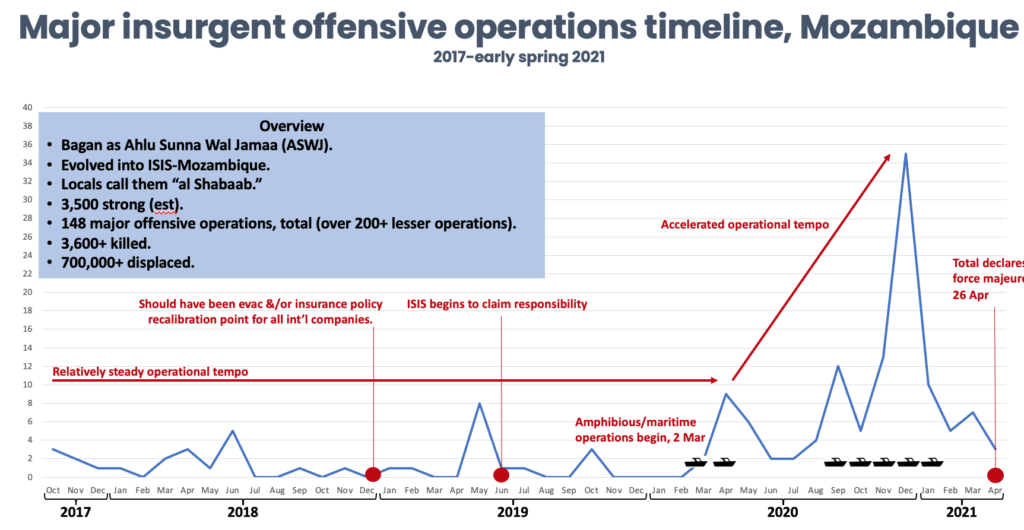

Operational tempo

From the last three months of 2017 to February 2020 – two years and six months – ISIS-Mozambique’s operational tempo for major operations was 1.23 a month on average. Most of these were village raids. Some of these months had no operations, and some had three or five. One had eight. Then, from April 2020 – April 2021, there were 8.69 major operations a month, on average. One month had 35.

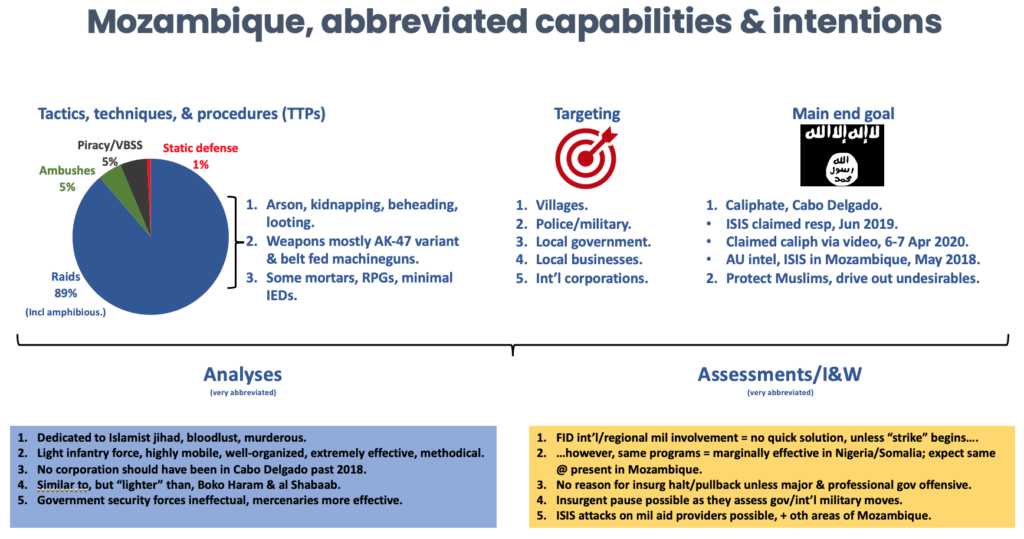

Raids

Most of these significant operations, about 148, were raids. These consisted of the insurgents gathering into one or several units, and, from one or more rally points, attacking a specific target, and then at an opportune time, egressing from that target. ISIS-Mozambique has occupied a few of its raid targets, and the group certainly occupies vast tracts of real-estate in Cabo Delgado for basing.

ISIS-Mozambique has conducted at least seven amphibious raids where its fighters gathered in boats and attacked various islands off Mozambique’s northeast coast.

ISIS-Mozambique has conducted both day and night raids. Raid formations have reportedly consisted of single groups of 10-20 fighters to multiple groups of 100-300. The latter has been part of multipronged attacks on large towns and a handful of military bases.

During raids, ISIS-Mozambique has demonstrated specific tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs.) These have included untold numbers of shootings/executing civilians, over 150 acts of mass arson, at least 19 mass beheadings, and more than 14 mass kidnappings of women and children. The word “mass” is used repeatedly here to demonstrate a point. Regional aid groups quoted by Reuters estimate the insurgents kidnapped as many as 51 children in 2020 alone. Kidnappings are presumably to secure child soldiers, brides for marriage, and for general sexual exploitation.

Looting food, fuel, vehicles, and banks in larger towns is common during ISIS-Mozambique’s raids. Its fighters make a habit of collecting weapons and ammunition from the police and soldiers they kill, as is common for most insurgencies.

Raid examples

The following cases exemplify ISIS-Mozambique’s standard operating procedures (SOPs) for raids. On 29 November 2017, its fighters raided Mitumbate village. Here, the attackers shot villagers, burned 27 homes, blew up a church with some kind of explosive or incendiary device, killed a man with a machete, and shouted at villagers to flee Cabo Delgado.

In a more gruesome raid on 6-8 November 2020 in Muatide, the insurgents beheaded 50 people on a soccer/football field and chopped up their bodies.

There have been several operations where the insurgents have burned 100 homes, such as the June 2018 attack on Namaluco village.

In January 2020, says Club of Mozambique, the insurgents raided a military base in Mbau, killing 22. They also stole two military vehicles and absconded with weapons and ammunition.

Muir Analytics covered one of ISIS-Mozambique’s amphibious raids in detail here. In this case, on 9 September 2020, insurgents boarded boats in the middle of the night and attacked the exclusive island resort of &Beyond Vamizi and the nearby civilian-inhabited island of Metundo. The resort had been evacuated of guests, and the insurgents torched its many bungalows. Muir warned that other hotel attacks were likely to occur.

Large raids on towns

ISIS-Mozambique has conducted at least four large raids on towns that required high-level planning and professional command and control. The targets were:

- The port town of Mocimboa da Praia, plus two nearby military bases (23 March 2020.)

- Macomia town (28 May 2020.)

- Kitaya village in Tanzania (14 October 2020.)

- Palma town (24 March 2021.)

1. The Mocimboa da Praia raid reportedly consisted of several hundred fighters converging on the town from three avenues of approach, including an amphibious approach from the sea. The attackers blocked off all roads leading into the town as well.

2. ACLED data used by Relief Webs reports that, at Macomia, the insurgents used as many 120 fighters wearing Mozambique military uniforms. They attacked the town from three directions, cutting off major roads leading in and out – by this point, SOP for the group’s major raids. They were armed with RPGs and brought with them a Chinese armored personnel carrier with a W85 heavy machine gun mounted on it. They overran government forces guarding the town. When helicopters from the mercenary Dyck Advisory Group (DAG) arrived to apply suppressive fire, the insurgents reportedly changed into civilian clothing to blend into the local population to confuse gunners and deny them targets.

3. The attack on Kitaya reportedly consisted of 300 fighters and included a forging operation across the Rovuma River, which serves as the border between Mozambique and Tanzania. The target town sits on the banks of the river. It is unclear how the insurgents crossed it or how deep and swift the water was or was not, but it happened at the end of the rainy season. Regardless, moving that many fighters across a river, swollen or otherwise, required professional military know-how.

As an aside, ISIS-Mozambique raided at least three other villages in Tanzania on 28 October 2020: Michenjele, Mihambwe, and, reportedly, Nanyamba – all about 20 miles west southwest of Kitaya. Nanyamba is about 10 miles from the Rovuma River. Michenjele and Mihambwe are but two miles from the river.

4. The raid on Palma initially consisted of 100 fighters that were later joined by 200 more. Some reporting suggests the insurgents engaged in pre-attack infiltration operations (most likely advanced force operations such as reconnaissance, target designation, and prepositioning of weaponry and small fighting units,) which might have preceded the other major town attacks as well. As with the other large town raids, the attackers blocked off all roads in and out of town.

The attack on Palma included the seizure of the Amarula Palma Hotel, where over 100 locals and foreigners had gathered, waiting for government rescue, but none came. Early in the Palma raid, helicopters from DAG managed to rescue several small groups of people from the hotel in their light-skinned helicopters before heavy insurgent fire forced them away.

Those who remained at the hotel organized two escape convoys, one of which had 17 vehicles that insurgents ambushed multiple times. Scores were killed under incredible duress while demonstrating extraordinary bravery. Only seven vehicles of this convoy made it to safety. When government forces finally reached the hotel days later, they found a shallow grave of 12 foreigners who had been beheaded, said several press reports.

Piracy/VBSS

Beginning in November 2020, the press began reporting in earnest on ISIS-Mozambique’s piracy. In military terms, these were Visit/Board/Search/Seizure (VBSS) operations. Muir Analytics counted at least eight such operations since then, but there might have been more. This could be a case where the press has suffered from a lack of access to Mozambique’s seafaring communities. At any rate, during these attacks, insurgents have stolen fishermen’s belongings, cell phones, and fish. In one case, they kidnapped several people.

Ambushes

ISIS-Mozambique has reportedly staged at least 14 ambushes, and likely more. Most of these entailed insurgents lying in wait by roads for government, civilian, or corporate convoys to come into their kill zones, upon which they opened fire, disabling the vehicles and killing as many as possible. The ambushers then kidnapped or killed the survivors – sometimes by beheading – and looted the vehicles or stole them. Sometimes, they set out logs as roadblocks to halt their target convoys. ISIS-Mozambique has also set up ambushes on government infantry forces and their supporting private soldiers – namely the Russia-based Wagner Group – in heavily vegetated areas to deadly effect.

A classic example of an ISIS-Mozambique ambush comes from 17 December 2017, where insurgents laid trees onto a road, which halted a column of the police’s Rapid Intervention Unit (UIR.) When UIR personnel got out to move the logs, the ambushers opened fire, triggering an hour-long firefight, which killed scores, including one of the most senior UIR officers.

Weaponry

Pictures, video, and some written reporting have revealed the different types of ISIS-Mozambique’s weaponry. Some of it might have been purchased on the black market, and much of it has come from captured Mozambique and Tanzanian military and police stocks.

The insurgents carry multiple variants of the AK-47, RPK, RPD, and PK machineguns. In some media, insurgents were seen carrying at least one HK-91 assault rifle and an M-4 style assault rifle, but these appear to be outliers. They also carry RPG-7s (or copies, such as the Chinese type 69 RPG) with several types of warheads, including what appear to be Chinese Type III 80mm high explosive anti-tank rounds (HEAT, effective against tanks, armored cars, buildings, and bunkers,) and Chinese airburst 75mm high explosive/fragmentation rounds (HE, effective against humans.)

The insurgents reportedly have a slew of mortars, brought in from outside Mozambique, say DAG personnel. Pictures of captured insurgent weapons show what looks like 82mm mortar rounds. The Mozambique military has 82 and 102mm mortars, however, so the insurgents could have secured these from the army. IHS Markit says the insurgents first used mortars during the raid on Mocímboa da Praia. Survivors from the Amarula Hotel attack report a constant barrage of mortars on the town – 40-50 rounds per hour – and DAG fighters say this occasion was likely the first time the insurgents used mortars to any great extent. They did not appear to use them on the hotel, however. If they had, the hotel would have suffered tremendous damage. The insurgents probably used them on Mozambique military and police targets and maybe on other civilian targets in town.

ISIS-Mozambique appears to have captured several armored cars or armored personnel carriers. The Actual Line of Control website did an excellent analysis on this and figured they were Mozambique armored police cars, specifically Chinese-made Shaanxi Baoji Special Vehicles Company Tiger 4×4 (ZFB05-G model.) It is not clear how many of these vehicles the insurgents might have.

Other weaponry the insurgents have includes the AGS-17 Plamya, which is a 30mm grenade launcher system, plus a wide array of pistols (Makarovs and Browning Hi-Powers/or Hi-Power clones,) homemade hand-thrown explosives (compound unknown,) arson kits, and maybe Russian (or Chinese) F-1 grenades.

Targeting

From the above trends, ISIS-Mozambique appears to prioritize targeting Cabo Delgado’s civilian population, especially Muslim and Christian villages that do not cooperate with its end goals. It moreover targets Mozambique’s police and military. The insurgents have also attacked all vestiges of national government they come across during their raids – town/regional administrative headquarters, health centers, banks, and the like.

ISIS-Mozambique has also attacked several foreign companies working in Cabo Delgado, including Japanese firm Konoike. It was repairing the N380 bridge over the Messalo river at the time. The insurgents have also attacked Fenix Construction that was working for Total, a Chinese sawmill in Mocimboa de Praia, &Beyond Vamizi island resort, and Anadarko Petroleum, which reportedly suffered several dead in two convoy ambushes. Scores of people working for a multitude of foreign companies were killed during the attack on Palma. Some of the latter, along with Anadarko, were working on the Total-led, $50+ billion offshore natural gas exploration and production operation off Cabo Delgado. Neither Total nor its other partners, such as ExxonMobil, have reported casualties, but they have all been forced to stop work on their gas project.

Intentions

Statements and information operations by Mozambique’s insurgents indicate their intentions. There have been at least 16 instances of the insurgents saying they are part of ISIS, or ISIS saying the insurgents are part of it. These have consisted of claims of responsibility for attacks in Cabo Delgado, occasions of ISIS flag raising during raids on towns, and ISIS graffiti painted on buildings in towns the group has seized. These cases strongly suggest the organization has ISIS-type goals – to establish an Islamist jihadist caliphate by preaching and violence. Examples follow.

The Counter Extremism Project (CEP) says that in May 2018, ASWJ insurgents released a photo of their fighters with a black and white Islamist jihadist flag behind them. They said they would soon pledge allegiance to ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. This did not happen until 2019, says CEP.

Following attacks on 13 and 15 January 2018, a group of six camouflaged insurgents on social media claimed responsibility for the violence and said they were fighting against “perverted values of Islamic doctrine.” They moreover said they were going to implement proper sharia law in the region. At the time of the claim, the Mozambique government could not authenticate the video’s legitimacy.

On 25 March 2020, Mozambique’s insurgents took over the town of Quissanga. From the government’s local headquarters, an insurgent leader, standing under the black and white flag of Islamist jihad, directly asserted that they were fighting to apply sharia law. They rejected by name the current government of Mozambique – the Liberation Front of Mozambique (FRELIMO.) The speaker moreover said, “We are not fighting over (the) wealth of the world,” indicating that taking over the natural gas project off the coast of Cabo Delgado was not their goal.

On 6 April 2020, insurgents occupied Bilibiza village and gave its residents a lecture, telling them, “We are occupying this village to show that the government of the day is unfair. It humiliates the poor to the advantage of bosses. Those who are detained are those of the lower class, so this is not fair. Like it or not, we are defending Islam. We want an Islamist government, not a government of unbelievers.”

A day later, when insurgents raided Ntchinga village, they reportedly did the same thing, and they made a video of their speech.

On 7 April 2020, the insurgents staged multiple raids on at least five villages, reportedly revenge operations for local Muslims not joining their Islamist jihadist movement.

Having said all this, the fact that there is a massive, $50 billion offshore natural gas project going on just off Cabo Delgado cannot be ignored. This area is also a lucrative smuggling route for drugs, weapons, and other goods. Scores of pundits have cited these two issues as major, hidden reasons behind the insurgency. Muir Analytics agrees with the supposition that the gas project and the smuggling routes are factors in the insurgent ecosystem. Minus corruption, revenues from the gas project could turn Mozambique into the Dubai of Africa. But the exact correlation between these factors and the insurgency remain elusive.

Land clearing

A key goal of the insurgents’ operations appears to be land clearing. Specifically, they seem to be getting rid of Cabo Delgados’ “undesirable people” – seemingly Christians and moderate Muslims. As previously stated, the vast majority of the insurgents’ raids have been against villages, which, again, has included mass arson against hundreds of homes. If they wanted these villagers as supporters, either forced or verbally convinced, they would not have burned their homes down.

Additionally, insurgents have been telling people to flee the areas they attack. In a raid on Mitumbate village in 2018, an eyewitness said, “They started to burn the houses screaming, ‘get out of here. We do not want anyone to live in this village.”

On 11 May 2019, near Mangoma village, insurgents captured a man, tortured him, and told him to run to the next village and tell them to abandon the area. In another instance, they attacked a funeral procession, killing two, and, according to an eyewitness, “They shouted at us to leave the village, saying, ‘We do not want anyone to live here. Why are you still here? Don’t you see that we’re at war?’”

From 30 September-6 October 2020, insurgents attacked the town Mucojo. They hoisted the Islamist jihadist flag, killed villagers, looted homes and businesses, and vandalized the place. They also told villagers to vacate the area, saying, “Go to Maputo and stay with your President Nyusi.” They even gave bus money to elderly villagers to provide them a way out.

Again, these types of operations have caused over 700,000 refugees to flee Cabo Delgado in the past four years. All of this is on purpose.

From ISIS-Mozambique’s view, Cabo Delgado’s undesirables include Christians, as ISIS claimed after the attack on Palma in March 2021. The frequent burning of churches adds credence to this supposition. Even insurgent raids into Tanzania have targeted Christians. After attacking the previously mentioned villages of Michenjele, Mihambwe, and Nanyamba on 28 October 2020, the Islamic State issued a claim the same day, saying their forces attacked three “Christian villages” in southern Tanzania.

Moderate Muslims appear to be on the insurgents’ list of undesirables as well. Human Rights Watch says that on 5 June 2018, for example, they attacked Naunde village, and aside from burning 164 houses, they also set alight the local mosque and beheaded the local Islamic leader inside the mosque.

Takeaways

First, if the number of ISIS-Mozambique insurgents is factual – 2,500-3,500 – (in military terms, about a regimental+-sized force,) they have enough personnel to control Cabo Delgado, especially if confronted with a passive population and a weak government security force. It also means they have enough fighters to attack, overwhelm, and occupy the Total gas project in Cabo Delgado.

Again, if these insurgent numbers are accurate, then by military standards, it would take a professional fighting force numbering at least three times larger to defeat them decisively. If the insurgency has taken firm root amongst the population, it will take a proficient counterinsurgency campaign and a force 15 times larger than the insurgency to defeat them. As of 2021, it does not outwardly appear the insurgency has taken firm root amongst the people.

Second, regarding operational tempo, the insurgents’ early operations (its first two years and six months) were intermittent but steady, indicating a cautious, methodical insurgency that was gaining experience and confidence as it was fighting. It was also probably testing government and international resolve and fighting ability.

The insurgents’ spike in operations after April 2020 suggests they had achieved that experience and confidence and, most likely, secured more recruits to surge operations. They also probably recognized that neither the Mozambique government nor the international community would present a significant threat, and audacity suddenly became an option for them.

Third, as far as TTPs are concerned, ISIS-Mozambique is a light infantry force capable of small, medium, and large-scale attacks on medium/small-size towns, military bases, police stations, and sparsely inhabited swaths of countryside. In military terms, the movement has demonstrated it is capable of squad, platoon, company, and battalion-sized operations. If ISIS-Mozambique does have 2,500-3,500 fighters, then, in theory, it can carry out regimental-sized operations. The insurgents always appear to bring enough manpower and firepower to achieve their goals.

ISIS-Mozambique has a demonstrated proficiency in raids, piracy/VBSS, and ambushes. Mass arson, looting, and group executions by machete are also part of its regularly used tactical tool kit.

As an aside, ISIS-Mozambique’s mass executions have been copious and particularly gory, indicating the group has a sociopathic blood lust. This is not uncommon in warfare in Africa – but certainly not exclusive to Africa – such as the Hutu takeover of Rwanda in 1994 and ongoing Hena vs. Lendu violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Africa has also seen gruesome, genocidal Islamist jihadist violence, such as the Algerian Civil War (1994-2002) and Boko Haram’s ongoing war in Nigeria and neighboring states.

Taking this brutality into consideration, Muir Analytics would have advised underwriters and insurance policyholders to vacate Cabo Delgado in December 2018 despite the insurgents’ slow operational tempo.

Fourth, the insurgency’s four large operations against medium-sized towns denote professional military command and control capabilities. The planners and field commanders of these operations have likely undergone professional military training, or other accomplished insurgents have tutored them, or are commanding them.

Fifth, based on the insurgents’ several forays into southern Tanzania, they are comfortable moving large formations across rivers, and they seemingly have had no problems with cross-border operations. They likely have intelligence sources in Tanzania and see it as an extension of their Cabo Delgado area of responsibility.

Sixth, the insurgents’ maritime raids and piracy/VBSS operations suggest they fully appreciate their coastal/littoral environment from a strategic perspective. It also means they also have in their ranks personnel with high-level boating experience – commercial experience for sure, military experience, maybe. Up to late spring/early summer 2021, ISIS-Mozambique appears to have achieved a degree of maritime control of Cabo Delgado’s coastal and island reaches, but not total control. Press reports have not indicated any lasting maritime picket or patrol capability.

Seventh, regarding weaponry, ISIS-Mozambique mainly uses Soviet/Russian/Chinese light infantry and shoulder-fired weapons, which are standard for similar insurgent movements in Africa and the Middle East. These weapons and are reliable and effective. Even in the hands of an average fighter, they can achieve deadly effects that significantly contribute to a movement’s end goals.

Eighth, because ISIS-Mozambique has concentrated on targeting civilians in Cabo Delgado (plus foreign companies,) and because its military-to-military (and police) clashes were seemingly against mostly mediocre forces, its fighters might not be genuinely combat tested. Primarily targeting civilians also provides insight into the insurgency’s intentions. See below.

Ninth, as far as ISIS-Mozambique’s intentions are concerned – civilian targeting, joining ISIS, land clearing operations, and preaching “proper sharia law” – the indication is that the movement aims to cleanse Cabo Delgado’s population and install an Islamist jihadist caliphate. Displacing over 700,000 people from Cabo Delgado proves they have experienced success in this regard. And, while the insurgents, or a faction of them, have stated that they are not interested in material wealth, the fact that this insurgency is active around one of the world’s largest offshore gas projects and a major regional smuggling route cannot be ignored. More evidence is needed, however, to draw any decisive conclusions on these specific issues.

Looking forward (threat indicators and warnings)

First, scores of regional and foreign governments have expressed interest in providing foreign internal defense (FID) aid to stem the tide of ISIS-Mozambique, including the US, South Africa, Rwanda, and others. Based on other such FID missions in Somalia, Nigeria, and Mali where the insurgent/terrorist situation is similar, FID offers no quick solution. If any of these FID providers begin strike missions, that is, in layman’s terms, missile and other ordnance attacks on insurgent/terrorist encampments, convoys, high-value targets (personnel,) etc., then the insurgents will be forced into a defensive posture, and they will likely curb their operations, at least in the immediate term.

Second, there will be no reason for ISIS-Mozambique to curb their offensive unless they face a major, professional ground offensive, or unless foreign forces surge into the country. If this happens, the insurgents might pause operations to assess the forces arrayed against them.

Third, ISIS-Mozambique has made threats against any country that comes to Mozambique’s aid. In Islamist jihadist jurisprudence terms, this serves as a legal warning to these countries, allowing for ISIS to attack them at a time of its choosing. Any government that helps Mozambique should increase vigilance – read, intelligence operations – and physical security measures against terrorist attacks.

Sources and further reading:

“Child kidnapping being used as warfare tactic in Mozambique, aid groups say,” Reuters, 8 June 2021.

“Mozambique: How a massacre unfolded,” Sky News, 11 April 2021.

“How Mozambique’s corrupt elite caused tragedy in the north,” The Africa Report, 11 April 2021.

“Terrorism in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province: Examining the data and what to expect in the coming years,” IHS Markit, 5 April 2021.

Tim Lister, “The March 2021 Palma Attack and the Evolving Jihadi Terror Threat to Mozambique,” VOLUME 14, Combatting Terrorism Center at West Point, APRIL/MAY 2021.

“Insurgents ‘better armed and organised’ in brutal Palma assault,” Upstream Online, 31 March 2021.

“Mozambique: Dozens dead after militant assault on Palma,” BBC, 29 March 2021.

“Rebels leave beheaded bodies in streets of Mozambique town,” Los Angeles Times, 29 March 2021.

“Isis claims deadly attack in northern Mozambique,” The Guardian, 29 March 2021.

“State Department Terrorist Designations of ISIS Affiliates and Leaders in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Mozambique,” US Department of State, 10 March 2021.

“The Islamic State in Mozambique,” Lawfare Blog, 24 January 2021.

“Cabo Ligado Weekly: 7-13 December 2020,” The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED.)

“An Islamist insurgency in Mozambique is gaining ground — and showing a strong allegiance to the Islamic State,” Washington Post, 13 November 2020.

“Militant Islamists ‘behead more than 50’ in Mozambique,” BBC, 9 November 2020.

“Mozambique: Terrorists attack Mucojo again – AIM report,” Club of Mozambique, 14 October 2020.

“The Men and the Machines: Mozambique’s Elite Motorized Infantry, Part 1: The Machines,” Actual Line of Control, 10 August 2020.

Tomasz Rolbiecki, Pieter Van Ostaeyen, Charlie Winter, “The Islamic State’s Strategic Trajectory in Africa: Key Takeaways from its Attack Claims, VOLUME 13, ISSUE 8,” Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, August 2020.

“‘SA private military contractors’ and Mozambican Airforce conduct major air attacks on Islamist extremists,” Daily Maverick, 9 April 2020.

“‘Legitimate’ jihadist video calls for Islamic law in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado – report,” Upstream Online, 27 March 2020.

“Cabo Delgado: Attack on Mbau causes several deaths, Islamic State claims action,” Club of Mozambique, 28 January 2020.

“Burning villages, ethnic tensions menace Mozambique gas boom,” Bloomberg, 2 July, 2018.

Caleb Weiss, Islamic State claims first attack in Mozambique, Long War Journal, 4 June 2019.

“Mozambique Islamists step up attacks after cyclone,” Modern Ghana, 29 May 2019.

“Burning villages, ethnic tensions menace Mozambique gas boom,” Bloomberg, 2 July 2018.

“Mozambique: Armed Groups Burn Villages,” Human Rights Watch, 19 June 2018.

“AU Confirms ISIS Infiltration in East Africa,” Uganda Radio Network, 23 May 2018.

“PRM desconhece suposto grupo terrorista fixado em Cabo Delgado e que apela para violência através de vídeo nas redes sociais,” Verdade, 31 January 2018.

“Rapid Intervention Force director killed in Mocimboa da Praia,” Club of Mozambique, 20 December 2017.

“Mais um ataque em Mocimboa da Praia,” Voice of America, 4 December 2017.

END

Copyright © Muir Analytics 2021